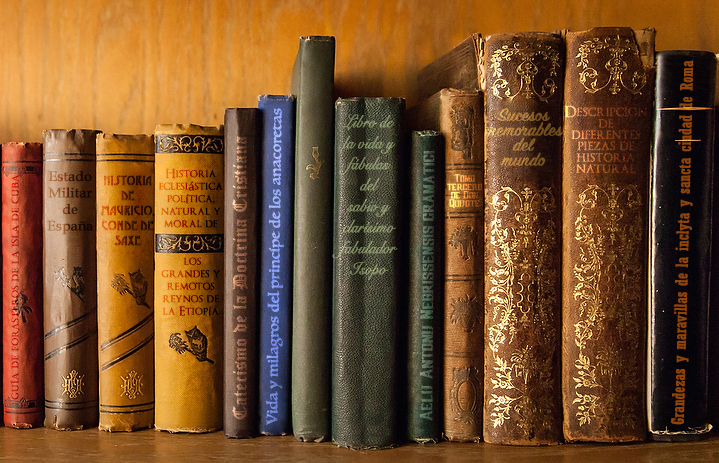

Click on any book spine to learn more.

When colonial Spanish officials searched Aponte’s home and workshop, they found his “book of paintings,” loose leaf images and documents, and also a small library. The library contained eleven books all “old and used,” recorded in the trial record as “one very elegant board book which is titled Descripción de Historia Natural, an Arte Nebrija, Guía de Forasteros de la Isla de Cuba, Maravillas de la Ciudad de Roma, Estado Militar de España, Sucesos Memorables del Mundo, Historia del Conde Saxe, Formulary for letter-writing, Catecismo de la Doctrina Cristiana, Vida del Sabio Hisopo and the Third Volume of Don Quijote” (Pavez Ojeda 2006a, 727). In addition, Aponte testified that he had loaned two other books that he used in the making of the “book of paintings,” “El libro de la vida de San Antonio Abad and El Libro del Padre Fr. Luis Yrreta” (Pavez Ojeda 2012, 273). Scholars Jorge Pavez Ojeda and Stephan Palmié have further identified possible versions of these books that Aponte owned. Click on any book spine in the image above to learn more. (We have left out of the above recreation the formulary for letter-writing.)

During the trial testimony, Aponte and his assistant Trinidad Nuñez, talk about using books that appear to have circulated amongst the community of free people of color. Aponte mentions learning from a “book of general history” through a “black man whose name he did not remember” who had arrived to Havana from Spain (Pavez Ojeda 2006a, 734). Trinidad describes using the book by Father Luis Yrreta to draw images on lámina 46 of the “book of paintings.” He says the book was currently in the possession of the “black woman Catalina Gavilan in Guanabacoa” (Pavez Ojeda 2006a, 751), indicating Aponte had loaned it to her. By 1791, seven printing presses operated in Havana, producing volumes like the Guía de Forasteros de la Isla de Cuba that Aponte owned, but we remain unsure if he would have been able to purchase books from such presses. He may have relied instead on those community networks that spanned the city and, in the case of the man from Spain, the Atlantic.

Jorge Pavez Ojeda singles out a few volumes from Aponte’s library as influential in his conceptualization of the “book of paintings.” First, he argues that volumes on historical Ethiopianism, including a history of Ethiopia and volume on San Antonio Abad, by scholars “who took it upon themselves to inform Europeans about the history of Abyssinia” echoes Aponte’s own mission in depicting and sharing his historical and artistic vision in colonial Havana (Pavez Ojeda 2012, 286). The authors of these books, Luis de Urreta and Juan de Baltasar, also actually appear represented in the book on lámina 29, along with other scenes of Ethiopianist imagery. (A note: Stephan Palmié identifies the San Antonio Abad as instead being by Joseph Navarro.) Additionally, Aponte’s assistant Trinidad Núñez testified that he used these two books as sources to paint certain figures (Pavez Ojeda 2006a, 751).

Secondly, Pavez Ojeda notes that the biography of Maurice of Saxe likely inspired Aponte’s many battle scenes, particularly because of “the prominence and fame of his battalion of black soldiers in the military successes of that well-known German freemason” (Pavez Ojeda 2012, 289). As examples, Aponte represents his grandfather and father defending the city during the British invasion of 1762 on láminas 18-19 and the army of the African king Tarraco invading Hispania on láminas 24-25.

The volume of Aesop’s Fables also reflects Aponte’s interest Greco-Roman mythology through his inclusion of a range of gods and goddesses in the “book of paintings.” Pavez Ojeda also pinpoints the Aponte’s uses of “aphorisms similar to those used by Aesop to denounce the ignominies of power,” to a moral framework, as on lámina 20 where a phrase relates that “death cannot destroy prudence” alongside a depiction of the “God of fables” (Pavez Ojeda 2012, 291). Similarly, the early modern guide to Rome, Grandezas y maravillas de la inclyta y sancta ciudad de Roma, perhaps impacted Aponte’s own development of a “monumental urban cartography” in his representations of locations and monuments in Havana(Pavez Ojeda 2006a, 754).

Lastly, Aponte’s possible ownership of Cuba’s first natural history, by Portuguese naturalist Antonio Parra, provided a visual contrast to Aponte’s own illustrious black history. Parra included in his volume three images of a free black man Domingo Fernández, who suffered from elephantiasis, as an example of the limits of nature. Aponte’s representations of black bodies offer heroic depictions in opposition to Parra’s “monster” (Pavez Ojeda 2012, 296).